Old Mother Hubbard 2012: The Defensive Tackles

>> 1.27.2012

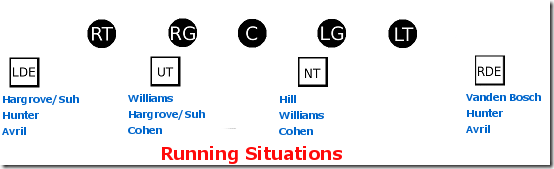

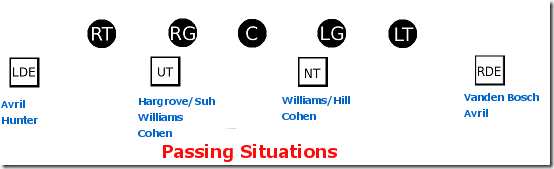

The Old Mother Hubbard series takes stock of what goods the Lions have left in the larder; i.e. the assets they have going forward. We’ll assess each player the Lions will likely bring to training camp. By tradition, we start with the defensive tackles and move away from from the ball. Here’s what last year’s Old Mother Hubbard had to say about each defensive tackle the Lions will be bringing forward:

Ndamukong Suh:

An incredible physical talent, with almost unlimited upside. As a rookie, he performed like an above-average starter, while carrying the heaviest workload in the NFL. If he continues to improve, Suh will become one of the best in the NFL—and maybe one of the best ever.Sammie Hill:

A natural big body who is slowly fulfilling his top-flight physical potential, Hill will remain a big part of the Lions’ rotation as his technique and body develop.Corey Williams:

Williams was a two-way force for the Lions in 2010, and an incredible addition to the roster. With his natural size (6’-4”, 320 lb.), great acceleration, and sometimes-too-quick snap anticipation, Williams is a difficult assignment for any offensive lineman. It would be really, really, really nice if he could cut down on the penalties.Nick Fairley, of course, was not around to OMH, and Andre Fluellen is an unrestricted free agent whose time seems to finally have come. Let’s see how Suh, Hill, Williams, and Fairley stack up against the league high, low, and average:

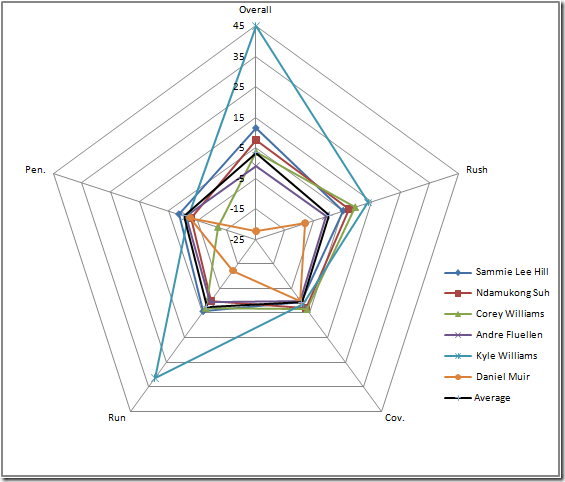

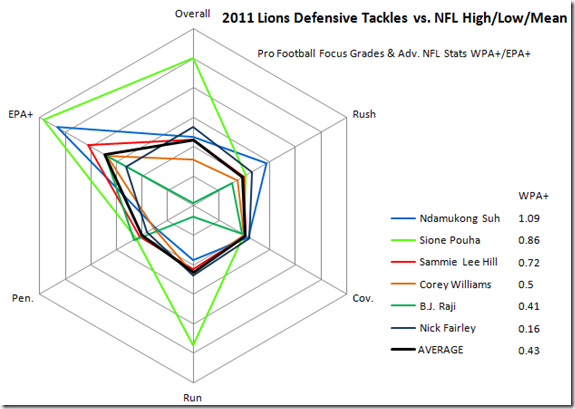

Ndamukong Suh is the perfect example of why I decided to add Advanced NFL Stats WPA+ and EPA+ data to this analysis. You can see that solid down-to-down run-stuffing combined with few-to-no penalties results in an extraordinarily high PFF grade, as with like the Jets’ Sione Pouha. Though Suh is the highest-graded pass rusher of this group at +8.6 (avg. -0.76), Suh’s overall grade is barely above league average at +3.3 (avg. +2.13).

This describes something true about Ndamukong Suh’s play: his -1.7 rush grade (avg. +2.45) means that most of the game, he’s doing a mediocre job of run stuffing and “pass coverage” (screen-sniffing-out). This is where EPA+ and WPA+ come in.

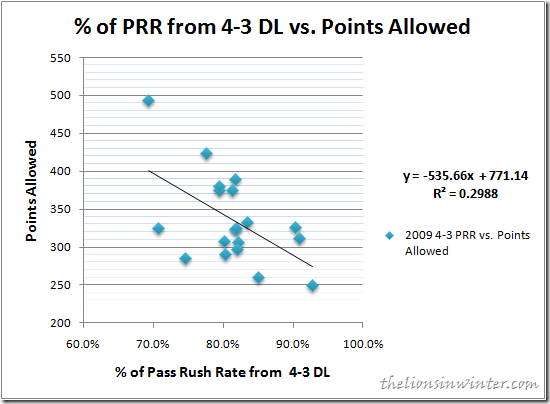

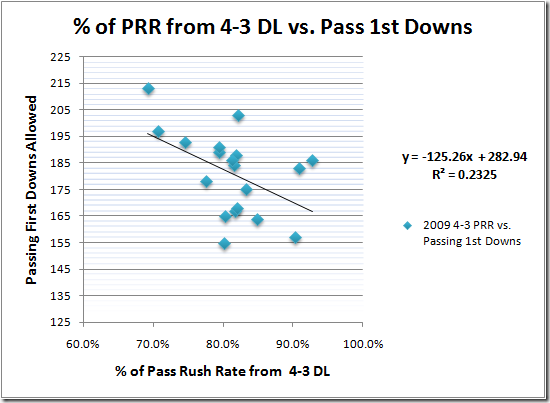

As Brian Burke of Advanced NFL Stats explains, EPA is a statistic that measures the Expected Points Added on offense: for each play made, how many points is that play worth (in his mathematical model)? Defensively, Burke measures performance with +EPA: he adds up “the value of every sack, interception, pass defense, forced fumble or recovery, and every tackle or assist that results in a setback for the offense.”

+EPA captures the positive impact a player has on his team—his playmaking ability. Generally speaking, the more and more-positive plays a player makes, the better he is relative to players who make fewer plays. To borrow a phrase, this accentuates the positive and eliminates the negative; +EPA can’t possibly measure defensive plays not made (Suh getting trap-blocked out of a play, for example).

There is an obvious connection between +EPA and high overall performance: Sione Pouha has the highest overall PFF grade, and the 6th-highest +EPA. But while Ndamukong Suh ranks 33rd in overall PFF grade, he’s 8th in +EPA. Suh is a “plus player,” to use scout’s parlance; he makes a dramatic positive impact on his team and the game.

Now, we turn to Win Probability Added. Again, Burke:

The model created here at Advanced NFL Stats uses score, time, down, distance, and field position to estimate how likely each team will go on to win the game. For example, at the start of the 2nd quarter, a team down by 7 points with a 2nd down and 5 from their own 25 will win about 36% of the time--in other words a 0.36 WP. On that 2nd down and 5, let’s say there is a 30-yard pass, setting up a 1st down and 10 on the opponent’s 45. Now that team has gone from a 0.36 to a 0.39 WP. The WPA for that play would be +0.03.EPA+ measures the expected points added by a defender’s positive plays, and WPA+ measures how much more likely a defender’s team is to win a game because of the positive plays he made. It makes sense that there’s a very high correlation between EPA+ and WPA+ (for this year’s DTs, it’s an r-squared of 0.883), but what WPA does is emphasize the game situation. A sack on 3rd and 6 is huge, but a sack on 3rd and 6 when you’re up by three late the 4th quarter is a lot huger than the a sack on 3rd and 6 when you’re up by 14 in the 1st.

So, back to Ndamukong Suh. He’s tied for eighth in WPA+ with 1.09; Pouha is 16th at 0.86. But wait, how can Suh have had a bigger positive impact on the Lions’ chances to win than Pouha, when Pouha’s PFF grade was literally ten times higher? WPA+ is a descriptive stat; it describes what happened in context—and in the case of defensive players, only describes their positive plays. Pouha was a devastatingly effective run-stuffer this year, and that’s it. He didn’t rush the passer, he didn’t pick off passes, he made tackles whenever they ran near him and didn’t screw up. That’s a formula for very high PFF grade, pretty high EPA+, and very good WPA+; exactly what we see.

There’s been a lot of talk about Suh’s reduced production this season. By PFF reckoning, he went from 11 sacks to 5, and from 48 tackles to 26. That came partially because of his lightened workload: in games he was active, he played 77.9% of snaps (of course, he was suspended for two games). In 2010 that figure was 90.4%.

The missing piece of the puzzle: stats that are not sacks. In 2010, Suh had 24 pressures and 6 QB hits. In 2011, Suh actually had more pressures, 27, and 4 QB hits despite being on the field for 224 (22.5%) fewer snaps. Suh actually had a sack, hit, or pressure more frequently in 2011 (avg. one per 22.1 snaps) than in 2010 (per 24.3 snaps).

Bottom Line: Ndamukong Suh is a fast, powerful pass-rushing tackle who impacts games about as dramatically as any DT in the NFL. His physical tools and competitive drive allow him to make huge plays at critical moments. His habit of taking bad personal foul penalties has come to a head and been addressed. His down-to-down consistency and run-stopping is improving, if slowly. In 2012, he needs to continue developing if he wants to reach his unlimited potential.

Sammie Hill had a 437-snap workload in 2011, and graded out at +2.5 overall, slightly above average. That’s a step down from 2010, when he received a +11.5 mark. From what I’ve seen on tape, they used Hill as the primary run-stopping tackle this year, and opposing lines are respecting that with double-teams. Hill is still learning how to handle this newfound attention, often getting dominated at the point of attack then using his strength to recover. His run-stopping grade went from +4.1 in 2010 down to +1.5 in 2011.

But like Suh, Hill had a positive impact much bigger than his PFF grade would suggest. His +WPA was 0.72, ranked 21st of 130 defensive tackles (and well above the 0.425 league average). His +EPA was 21.1, ranked 28th and nearly splitting the difference between Suh's 33.1 and the NFL average of 14.5.

Looking at the radar chart above, it's hard not to notice the Lions DTs hugging tightly to the NFL average in PFF grades, but flying way out towards the maximum in EPA+.

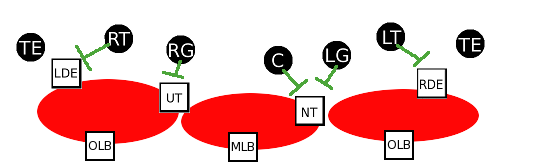

This confirms everything we think about the design of the Lions defense: they coach the linemen to get upfield and make plays, at the expense of typical DL responsibilities. Graded by traditional expectations of defensive linemen, they are mediocre. Graded by how they impact the game, they are outstanding. The whole picture takes both perspectives into account.

Bottom Line: Sammie Hill's is a powerful run-stopping DT with surprising athleticism. His role is growing, and his body and technique must scale with the challenge of his new responsibilities. He must learn to anchor against, or split, double-teams in the run game to take the next step.

Corey Williams needed to cut down on the penalties; he did, from 15 flags drawn in 2010 to just 8. However, he also cut down on the pass-rushing effectiveness. He went from a +9.2 PFF pass rush grade in 2010, down to -2.6. While his coverage and run-stopping grades held steady, cutting his penalties half only made him tied with Suh for third-most penalized DT in the NFL. His 0.5 +WPA and 13.8 +EPA closely match the NFL average for those stats, in a system that maximizes those metrics for DTs.

The ridiculous number of flags tossed his way were worth it when he was a dominant two-way player, not so when he's the least-effective pass rusher on the team. This is his contract year; I would not be surprised if 2012 is his last season in a Lions uniform . . . or if 2011 was.

Bottom Line: Corey Williams had an incredible 2011, arguably a better all-around performance than Ndamukong Suh's studly rookie year. But his pass-rushing performance fell off the face of the Earth when he stopped jumping snap counts, and he's still penalized far too often. If he does not recover some semblance of his 2011 form, he should (and will) be replaced.

Nick Fairley was a DT prospect nearly as beguiling as Ndamukong Suh; after the 2010 bowl season he was the consensus No. 1 overall prospect. Questions about his short on-field track record, his struggle with grades, and his off-field choices lingered, as did those about his long-term commitment to excellence. In the short term, it appears "excellence" is what he's all about.

His 236 snaps were just barely shy of PFF's 25% minimum threshold. If you discount that, Fairley was the Lions' top-graded overall defensive tackle in 2011. His pass rush, pass coverage, and run-stopping grades were all nicely positive, though he was assessed three penalties in those snaps, a poor rate going forward.

Fairley breaks the mold for Lions defensive tackles: he is consistently outstanding in every traditional phase of the game, nearly every down he plays. However, his low snap count and his lack of pursuit game have prevented him from generating enough "flash plays" to shine in metrics like +WPA and +EPA. This will change.

Bottom Line: On the field, Nick Fairley was everything the Lions could have asked for. His size, power, and desire to be great showed through every time he stepped on the field. Unfortunately, a foot injury slowed him at the beginning and end of the season. If he can stay healthy, and continue to develop his "country strong" physique, he could be a monster in 2012.

Overall, the Lions defensive tackles look deep and strong for 2012. Suh and Hill retrenched a little in 2011, but in the context of added responsibility. In very limited time, Nick Fairley was no less dominant in the NFL than in college. Corey Williams, though, had a relatively awful year, and the Lions must make a decision about him.

The Lions need three strong tackles to rotate, and a fourth for depth/development. If Williams is no longer a part of the top three rotation, he could be let go in favor of someone younger. Then again, if he's let go Hill becomes the graybeard of the group at 25. The Lions would also then rely on Hill to realize his potential as a dominant one-technique DT. The Lions may want to keep Williams for his veteran presence, if nothing else.

SHOPPING LIST: Nothing needed here, unless the Lions choose to jettison Williams in favor of someone younger/cheaper. Read more...