The Defensive Line and the Secondary, Part III

>> 7.23.2010

Throughout the offseason, it’s been speculated that the Lions’ woeful pass defense will get a boost from the revamped defensive line. With Kyle Vanden Bosch and developing Cliff Avril on the ends, and Corey Williams and Ndamukong Suh joining Sammie Hill on the inside, the pass rush should be greatly improved. This should, in turn, take pressure off the unproven secondary . . . right?

I set out to investigate this in part one, using the NFL’s league-wide data over the past two decades or so. I tried to find correlation between seasons when sacks were up, and seasons when passing offense was down. I think I learned more from the comments about how statistics and regression analysis work, than I did about the correlation between pass rush and pass defense—but my early results suggested that there is not a correlation between pass rush and pass defense.

I tried again with part two, blending pro-football-reference.com’s official and official-derived data for 2009, with profootballfocus.com’s manually film-reviewed defensive stats and grades. I came up with a stat I called “pass rush rate,” which was opponent pass dropbacks (attempts + sacks) divided by cumulative sacks, hits, and pressures. Then, I ran a simple correlation between every team’s pass rush rate for 2009, and their yards-per-attempt allowed. The correlation was weak, –0.152. When squared to get the effect size, it was a negligible .023.

Importantly, the real-world analysis bore this out: the Jets had an extraordinary pass defense, by far the best in the NFL. While their pass rush was solid, ranking 9th of 32 in pass rush rate, it was just that—solid, not phenomenal like the overall pass defense was. Amazingly, the Cleveland Browns generated pressure on the quarterback more often than every team except Dallas and Minnesota—and yet, they were the fifth worst pass defense in the NFL! Pass rush alone doesn’t make a defense effective.

For this installment, I wanted to get even more specific: I wanted to isolate defensive line pass rush from everything else. After all, the idea is that getting an effective rush with just the front four will allow much greater flexibility in coverage and blitzing. I aggregated the stats of just the defensive linemen, and compared them to what I already had.

Now, let me tell you a legendary tale . . . or, well, I guess, just a legend:

- Name: The name of the team.

- A: The primary defensive alignment.

- Pass Rush Rate: The percentage of opponent dropbacks (Attempts + Sacks) on which the defense achieved a pressure stat (Sacks + QB Hits + Pressures + Batted Passes).

- DL Pass Rush Rate: The percentage of opponent dropbacks (Attempts + Sacks) on which the defensive line achieved a pressure stat (Sacks + QB Hits + Pressures + Batted Passes).

- % of rush from DL: The percentage of defensive pressure stats (Sacks + QB Hits + Pressures + Batted Passes) generated by defensive linemen.

| NAME | A | Pass Rush Rate | DL Pass Rush Rate | % of rush from DL |

| Dallas Cowboys | 3-4 | 48.2% | 18.2% | 37.8% |

| Minnesota Vikings | 4-3 | 47.7% | 38.9% | 81.7% |

| Cleveland Browns | 3-4 | 44.0% | 19.1% | 43.4% |

| Miami Dolphins | 3-4 | 43.3% | 36.0% | 83.1% |

| Philadelphia Eagles | 4-3 | 43.1% | 35.4% | 82.2% |

| New York Giants | 4-3 | 43.0% | 35.3% | 82.0% |

| Atlanta Falcons | 4-3 | 42.9% | 35.1% | 81.8% |

| Green Bay Packers | 3-4 | 41.6% | 13.5% | 32.5% |

| Pittsburgh Steelers | 3-4 | 41.3% | 10.1% | 24.4% |

| Houston Texans | 4-3 | 41.2% | 32.7% | 79.4% |

| New York Jets | HYB | 40.3% | 19.3% | 47.9% |

| Denver Broncos | 3-4 | 39.7% | 13.1% | 33.0% |

| Tennesee Titans | 4-3 | 39.6% | 36.0% | 90.9% |

| San Francisco 49ers | 3-4 | 39.4% | 16.5% | 41.9% |

| Washington Redskins | 4-3 | 39.2% | 29.2% | 74.5% |

| Carolina Panthers | 4-3 | 39.2% | 35.4% | 90.3% |

| Arizona Cardinals | 3-4 | 38.5% | 18.7% | 48.6% |

| New England Patriots | HYB | 37.8% | 18.8% | 49.8% |

| Chicago Bears | 4-3 | 37.3% | 29.9% | 80.1% |

| San Diego Chargers | 3-4 | 37.3% | 12.5% | 33.5% |

| Kansas City Chiefs | 3-4 | 37.1% | 12.8% | 34.5% |

| St. Louis Rams | 4-3 | 37.0% | 28.7% | 77.5% |

| Oakland Raiders | 4-3 | 36.6% | 30.5% | 83.3% |

| Tampa Bay Buccaneers | 4-3 | 36.3% | 29.6% | 81.6% |

| Indianapolis Colts | 4-3 | 35.8% | 33.2% | 92.8% |

| Baltimore Ravens | 4-3 | 35.6% | 25.2% | 70.7% |

| Seattle Seahawks | 4-3 | 34.2% | 27.2% | 79.4% |

| New Orleans Saints | 4-3 | 34.2% | 23.6% | 69.2% |

| Buffalo Bills | 4-3 | 32.5% | 27.6% | 84.9% |

| Cincinnati Bengals | 4-3 | 32.2% | 26.2% | 81.3% |

| Detroit Lions | 4-3 | 29.2% | 23.5% | 80.2% |

| Jacksonville Jaguars | HYB | 27.9% | 10.3% | 37.0% |

We can see a few things in action here. First, the Lions were terrible: second-worst in the NFL in Pass Rush Rate. Second, the numbers get more wildly varied from left to right. Most teams generate a pressure stat on 30-40% of the time their opponents drop back to pass, with the extremes at 27.9% and 48.2%. Most teams generate pressure from the defensive line between 15-35% of the time, with extremes at 10.1% and 38.9%. The percentage of the pass rush that comes from the defensive line is all over the board, from 92.8% all the way down to 24.4%. What does this mean?

Given the amazingly wide range of percentage-of-pass-rush-from-defensive-line stats, and the zero (okay –.120, R-squared .014) correlation between them and Pass Rush Rate, I knew that scheme was a major factor. The Colts generated almost all of the pass rush from the defensive line, just as a Tampa 2 is supposed to. Their two ends, Robert Mathis and Dwight Freeney, accounted for 24 of Indy’s 33 sacks, 23 of 45 hits, 78 of 139 pressures, and 1 of 4 batted balls. That’s right, Mathis and Freeney were fifty-seven percent of the Colts’ pressure statistics; they were the Colts’ pass rush. Meanwhile the Steelers, despite having one of the league’s better pass rushes, got only 24.4% of their rush from their line.

I separated the teams out by scheme, grouping 4-3 teams together, and 3-4 and hybrid teams together. Since the Lions are a 4-3 team, and that’s what this exercise is all about, I discarded the 3-4s and the hybrids, and set about correlating PRR with Y/A, for just 4-3 teams:

Okay, so these are the 2009 4-3 defenses, and their overall Pass Rush Rate regressed against opponent Yards per Attempt. Look at the R-squared; there is literally zero correlation between these two statistics. Okay, we expected that to an extent—but what if we do it for just defensive line? If the rush is getting there without blitzing, that should make coverage better—so, we should see a tighter correlation when we regress DL-only Pass Rush Rate against Y/A Allowed:

That’s a little itsy bit better, but there’s still no real correlation happening here. Okay, what if we do it for percentage of pass rush that comes from the defensive line?

Okay, we’re making tiny, tiny incremental progress, but this is still nothing we can call correlation. Yards per Attempt, my favorite measure of per-play passing effectiveness, is completely disconnected from pass rush, DL-only pass rush, and percentage of pass rush generated by the DL. But we know for a fact that teams with good pass rushes have good defenses, right? I mean, the Vikings have a good defense, right? Right.

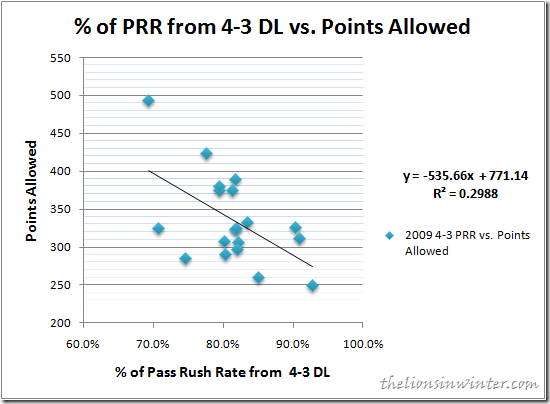

Okay, now we’re talking. In all of my pass rush data mining, the strongest meaningful correlation I could find was between what percentage of pass rush comes from a 4-3 defensive line, and how many points that defense surrendered on the year. As I said way back in part one:

We're left with the depressing conclusion that the only good pass defense is good pass defense. However, that's not really the case, either. Sacks and interceptions, though they don’t affect the interplay of pass offense and pass defense outside of themselves, are still extremely important in terms of total defense. Stopping drives and preventing scoring is the primary job of a defense; a third-down sack or a red-zone INT can erase sixty or seventy yards’ worth of Montanaesque passing effectiveness.

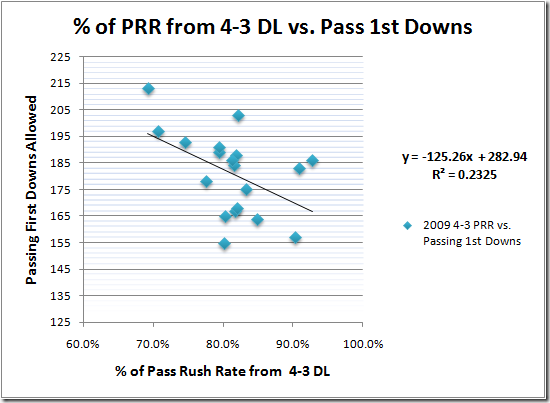

So again, as I’ve been saying: an improved pass rush won’t improve a team’s pass defense—but it will improve the team’s scoring defense. Here’s the second-strongest correlation I found: percentage of PRR from a 4-3 DL regressed against Passing 1st Downs Allowed:

Okay, again, this makes sense: the more pass rush you can generate from your 4-3 defensive line, the fewer passing first downs you allow . . . but we’re not done yet. I calculated the simple correlation factors for every offensive stat I thought might be illuminating. Note that these are NOT the R-squared effect sizes you see in the charts above—since that eliminates the direction of the correlation, which is important here. To get those effect-size figures, square the amounts in this table:

| Category | %DB/P | %DB/DLP | %P/DL | Att/PD |

| points | -0.133 | -0.360 | -0.547 | |

| total first downs | -0.007 | -0.210 | -0.431 | -0.262 |

| passing first downs | -0.015 | -0.241 | -0.482 | -0.132 |

| running first downs | -0.187 | -0.257 | -0.232 | -0.114 |

| yards per attempt | -0.064 | -0.139 | -0.190 | -0.062 |

| yards per completion | -0.147 | -0.316 | -0.418 | -0.293 |

| completion percentage | 0.135 | 0.269 | 0.325 | 0.356 |

| interceptions | -0.133 | -0.081 | 0.037 | 0.165 |

| touchdowns | 0.175 | 0.205 | 0.123 | 0.134 |

| passer rating | 0.156 | 0.148 | 0.049 | 0.012 |

Look at completion percentage: there is a weak, but positive correlation between PRR, defensive line PRR, and percentage of PRR from DL and completion percentage. So, as the defensive line gets more pressure, generally quarterbacks complete more of their passes—but, at what cost? Look again at yards per completion; there’s a moderate negative correlation between increased DL pressure and average completion length.

There is a definable “cringe effect!” When the defensive line generates more pressure, offenses generally tend to complete more and shorter passes—“going into a shell,” as it’s called. It’s this mechanism, completing more passes for fewer yards, that explains why yards-per-attempt allowed doesn’t change as the pass rush rate increases. Teams will dink-and-dunk in the face of the rush—meaning they convert fewer third downs, and score fewer points.

So. How much better will the Lions’ defensive line have to be? Well, as we saw, their pass rush numbers are terrible. In order for the Lions to improve their Pass Rush Rate to the league average, they’d have to increase it from 29.2% of snaps to 37.7%. To increase DL PRR to league average, they’d have to increase it from 23.5% to 30.7%. The percentage of PRR from the DL is about right, 80.2% versus 81.3%.

The league average team faced 567 dropbacks last year, compared to the Lions’ 571, so I’ll normalize the Lions’ pressure stats to 99.3%: 22.83 QB sacks, 34.76 QB hits, 100.29 QB pressures, and 7.94 batted passes. I’ll do the same for the DL pressure stats, from 18 to 17.86, from 26 to 25.82, from 82 to 81.43, and from 8 to 8.94. Now, to compare to the NFL average, find the difference, and voila:

| Team/Data | %DB/P | %DB/DLP | %P/DL | QBSk | QBHt | QBPr | BP | DLSk | DLHt | DLPr | DLBP |

| Detroit Lions (normalized) | 29.2% | 23.5% | 80.2% | 22.83 | 34.76 | 100.29 | 7.94 | 17.86 | 25.82 | 81.43 | 7.94 |

| NFL Average 4-3 | 37.7% | 30.7% | 81.3% | 33.00 | 52.00 | 118.00 | 10.00 | 25.00 | 40.00 | 98.00 | 9.00 |

| Delta (absolute) | 8.5% | 7.2% | 1.1% | 10.17 | 17.24 | 17.71 | 2.06 | 7.14 | 14.18 | 16.57 | 1.06 |

| Delta (percentage) | 29.1% | 30.6% | 1.4% | 44.5% | 49.6% | 17.7% | 25.9% | 40.0% | 54.9% | 20.4% | 13.3% |

We can conclude that, in order to bring their pass rush up to NFL average levels for a 4-3, their defensive line will have to increase their sack rate by 40%, their hit rate by 54.9%, their pressure rate by 20.4%, and their batted-ball rate up by 13.3%—and they’ll need a few more sacks and hits from the linebackers and secondary, as well. I’m still working on projecting all that data out into points allowed, first downs allowed, etc., but there you have it. If the Lions face the same number of dropbacks in 2010 that the average NFL team did in 2009, the difference between KVB/Avril/Williams/Suh and Avril/Hunter/Cohen/Hill will have to be worth an improvement of 7 sacks, 14 hits, 17 pressures, and 1 batted ball over 2009’s 18, 26, 82, and 8 to get back to average.