The Defensive Line and The Secondary

>> 5.26.2010

Lions fans worrying about the secondary have been closing their eyes, clicking their heels, and chanting, “The defensive line, the defensive line, the defensive line.” They’re telling themselves the additions of Kyle Vanden Bosch, Corey Williams, and Ndamukong Suh will drastically improve the pass rush, thereby shortening the field for the secondary. They’re telling themselves that opposing quarterbacks won’t have time to attack Chris Houston, Jonathan Wade, and Amari Spievey.

Are they telling themselves the truth? Can an improved pass rush really hide substandard secondary play? How much better would the defensive line need to be to cover up the lackluster coverage?

First, I went to my favorite NFL stats database, Pro-Football-Reference.com. I decided to go back to 1982, the year the league started keeping track of sacks as an official stat. I started with my favorite metric of passing efficiency, net per-play yards per attempt. The idea, if I understand correctly, is to measure the mean yards gained on every dropback.

So, my first task was simple: plot the correlation between sacks, and net-per-play yards attempt. This should show us if there is indeed a correlation between pass rush effectiveness (expressed in sacks), and depressed passing efficiency. There is a critical assumption, though:

- We assume that if sacks per dropback are significantly up or down across the NFL, there has been an increase or decrease in total pass rush effectiveness that season.

Wow, that looks pretty good right there! It sure looks like there’s a nice little cluster around the trend line, and . . . wait. What’s that one lonely data point all down there by itself? Ah, it’s 1982, the strike year. That explains it: since they only played nine games, most stats were just about halved, including sacks.

. . . wait. I used the wrong values. The total, leaguewide number of sacks will vary with number of attempts. In years where teams ran fewer plays, or passed less often, the number of total sacks would be lower—but that wouldn’t mean there was a decrease in pass rush effectiveness. No, what we want is sack rate; how often running a pass play results in a sack. I switched the X axis to average number of attempts per sack, and tried again. Remember, the hypothesis is that in years where sacks occurred more often, NY/A should be depressed.

The coefficient of correlation here is .451. For those of you who, like me, remember nothing of the high school math you didn’t understand at the time anyway: zero is no correlation at all, and 1 is perfect correlation. I’m not a statistician; I don’t know how to determine if this correlation is “statistically significant,” quote-unquote, but it seems fairly strong, and is definitely nonzero.

However, we have a problem: “Net Yards per Attempt” includes sacks. It’s attempts plus sacks, over passing yards minus sack yards. The higher the sack rate, the more passing yardage will be depressed—so our correlation is artificially enhanced.

Removing sack yardage from the equation, here’s the same chart:

Now our chart looks nearly random. The correlation coefficient is .068; approaching zero. Our hypothesis, that there is a correlation between increased pass rush and depressed passing effectiveness, is in rough shape.

There’s some data I’d really like to have that I don’t, namely “QB hurries” or “QB pressures”. These are plays where the pass rush was disruptive, but didn’t result in a sack. Unfortunately, that data isn’t official, and is likely to be quite subjective even if we had it. So, going forward:

- We have found that there is no inverse correlation between that pass rush effectiveness and passing effectiveness; on plays where a sack does not occur, per-play pass yardage is unaffected.

However, we know that there is such a thing as "good pass defense." If a pass rush that’s getting more sacks isn’t it, then what is? The first answer that springs to mind is “a defense that gets lots of interceptions,” right? So, here’s interception rate per attempt, against raw yards per attempt:

Ugh, another scattershot plot. The correlation is –.091, again nonzero but not strong. Again we see: interceptions are certainly a good thing to get, but a defense that gets a lot of interceptions isn’t necessarily a “good pass defense”. Just as with sacks, when you’re not actually picking a pass off, a high interception rate doesn’t help you much.

- We have found that there is no inverse correlation between interception rate and passing effectiveness; on plays where an interception does not occur, per-play pass yardage is unaffected.

So again, if there’s such a thing as “good pass defense,” is there a stat that directly correlates to it? Yes, I think there is: passes defensed.

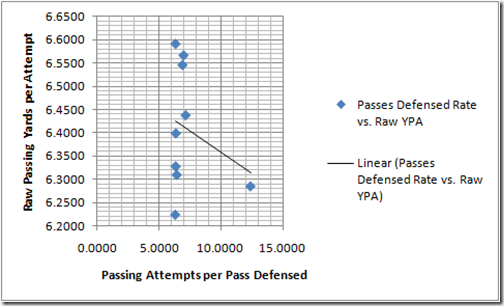

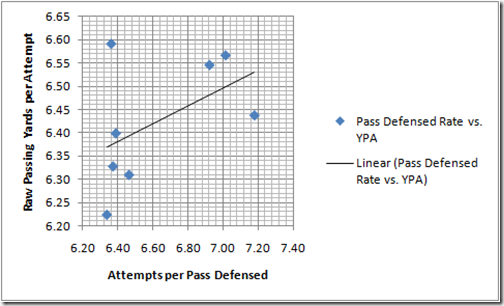

Unfortunately, it's only been tracked since 2001—and in 2002, the total number of passes defensed, league wide, was about half of what it’s been in every other year. I don’t know what happened there, but you can see it on the chart:

Yeah, that’s an outlier. Given that it was only the second year of tracking the statistic, it’s not unexpected. We drop it, and:

Ah-HA! The correlation coefficient is .495, and we see a clear trend emerging. We only have eight data points, but there’s correlation that isn’t built-in: on plays where the quarterback threw the ball forward, the more frequently passes were broken up, the less effective pass offense was, and vice versa.

One might point out that a pass defensed is an incomplete pass, so greater numbers of them necessarily lower YPA—but the same is true of interceptions, and we saw no such correlation above. The sample size is also troubling, in terms of establishing a statistical trend—but remember, each data point represents every passing attempt in the NFL for an entire season.

- We have found that there is a correlation between passes defensed and passing effectiveness; on plays where a pass is not defensed, per-play pass yardage is still depressed.

- We can assume that if passes defensed per pass attempt are significantly up or down across the NFL, there has been an increase or decrease in total pass coverage effectiveness that season.

We're left with the depressing conclusion that the only good pass defense is good pass defense. However, that's not really the case, either. Sacks and interceptions, though they don’t affect the interplay of pass offense and pass defense outside of themselves, are still extremely important in terms of total defense. Stopping drives and preventing scoring is the primary job of a defense; a third-down sack or a red-zone INT can erase sixty or seventy yards’ worth of Montanaesque passing effectiveness.

What's happening here? Follow the blue line, passing YPA. See the big dip it took in 2003? And the subsequential huge spike in 2004? That was a result of the Ty Law Rule, a change in the enforcement of Pass Interference and Illegal Contact rules. It’s named for the extremely effective, physical press coverage that Ty Law and the Patriots popularized in 2001, 2002, and 2003. The refs were “letting them play,” and the result was that passing was depressed.

In 2004, though, the refs started throwing the hankies, and passing effectiveness exploded as the press corners backed off. As teams could no longer afford to let their corners maul wideouts one-on-one, more safeties had to be rolled over to help. As more safeties rolled over to help, tight ends, backs, and slot receivers flourished. As more tight ends, backs, and slot receivers have flourished, more and more teams have switched from 4-3 fronts and man-to-man coverage, to 3-4/4-3 hybrids and zone coverage.

The upshot is that passing is getting more and more effective. Schemes are more complex, quarterbacks are sharper, and multi-back, multi-WR sets—difficult to defend with a traditional press defense—are forcing defenses to attempt aggressive, flexible disruption, with a broad safety net, rather than lining up 11-on-11 and winning battles.

What does this mean for the Lions? Likely the obvious: we’ll see lots more pressure, including lots more sacks, and that will improve the scoring defense—though not by nearly as much as is needed for the Lions to be a consistent winner. Ndamukong Suh and Kyle Vanden Bosch will not make the secondary any less porous, and teams—when they get a pass off—will still torch the Lions for long gains with great regularity.

Real statisticians, please, please, enlighten me in the comments.

UPDATE: I’ve followed this article up with Part II and Part III, drilling down much farther and finding really interesting stuff; check them out.

23 comments:

The only fault in the logic, which I find is a fault when dealing with pure statistics, is there are far too many unmeasured variables. You touched on it briefly when you said you would like to see the number of QB pressures or hurries, and I think that is the root of the problem with a pure statistical analysis. It has been said by numerous sources that even the best cover corner cannot effectively cover his man for more than a handful of seconds after the snap. By that reasoning, if we had Revis and C. Baily back there last year, would they have turned us into a strong defense? Perhaps, because the argument can also be made that the longer a corner can cover, the more time the line has to rush. Back to the very subjective stats of QB hurries and pressures, what constitutes a hurry or pressure? Is letting a QB get to his third read on a 3-step drop different than only letting a QB get to his first or hot read in a seven step drop, even though the same amount of time may have elapsed? The argument basically comes down to two perspectives: either the secondary helps out the line by holding coverage to force coverage sacks, or the line helps out the secondary by limiting the QB reads. By this reasoning, depending on which logic you follow, the Lions will either do great or be horrible, no in-between. The only way I think we have any shot at statistical analysis is a multivariable study, processing not only NY/A, sacks, and QB hurries/pressures, but also other factors such as effectiveness of run defense (which would force safeties to play closer if the line is poor), safety pressure, and linebacker plays. Theoretically, a good line would allow linebackers to drop into zones, the safeties to cover the top, and the corners to run with their men. Meanwhile, a poor line would force everyone to help the line, leaving the corners on an island, which as we know happened consistently last year. If our line this year can be as autonomous and effective as we all hope, I believe we will see great improvement in all levels of defense. Either that or another failed secondary unit gives way too much of a cushion and allows the big holes we saw last year, and the line is rendered impotent by lack of time. I for one would not mind hearing talk about how much our secondary has magically improved this year, when it is our line that is giving QB's sleepless nights and hurried throws.

A couple quick (for me) comments:

First, nice piece. A very interesting statistical approach to pass defense effectiveness, even if it didn't establish any hard, fast rules.

Second, correlations. In the scientific studies that I am familiar with (mainly social science-type stuff), you can more or less break the "strength" of a correlation into 5ths. 0.0 to 0.20 is no correlation. 0.20 to 0.40 is a decent correlation. 0.40 to 0.60 is a strong correlation. 0.60 to 0.80 is a very strong correlation (researchers do backflips if they find a correlation this high). 0.80 to 1.00 is an extremely strong correlation (and virtually impossible to achieve).

My third point follows from the second and requires a quote from above:

"However, we have a problem: “Net Yards per Attempt” includes sacks. It’s attempts plus sacks, over passing yards minus sack yards. The higher the sack rate, the more passing yardage will be depressed—so our correlation is artificially enhanced."

You found a .451 correlation between NY/A and Sacks, but say it's artificially enhanced. I don't think it's "artificial" at all. The yards lost to Sacks SHOULD be included because this is exactly what you're trying to examine - How does the pass rush (measured in terms of Sacks) affect passing efficiency (measured in terms of NY/A)? When you removed the Sack yardage, you basically removed your independent variable from the equation and, not surprisingly, your correlation dropped to near-zero.

Fourth, I don't remember off-hand how to verify "statistical significance," but I can find out and get back to you. Or maybe there's someone else who's a little more schooled in statistical analysis methods than I am who will read this and fill you in. Overall, though, I think your .451 correlation indicates that pass rush decreases passing efficiency.

Finally, to address Big Slim's comments about pass rush vs. secondary play, I think it's clear that it's a two-way street. Better pass rush helps the secondary and a better secondary helps the pass rush. Which has the greater impact is a matter of debate, but I would say pass rush is the stronger factor. This is all passed purely on my own subjective observations and "common sense," though, so take it for what you will.

In my last sentence, "passed" is supposed to be "based." I should really proof-read BEFORE I hit the Post Comment button. :-)

in another method to madness, and i have know idea if even feasible, would be if there is a higher rate of passes defensed to sacks.

ie. if the avg nfl game has 3 sacks and 3 passes defensed...

what happens with passes defensed if there are 4,5 sacks or 1 0r 2 sacks ???

hmmmmmm

Big Slim--

Well said.

I've never really believed in a purely statistical approach. To me, there's value in informed, impassioned observation. However, I know from aforementioned high school math that there are absolute truths--especially when it comes to probability and statistics--that are wildly counterintuitive.

The reason I tried to take a purely dispassionate, statistical approach on this one, because every time I mentioned that fact that the Lions' secondary is, at best, a totally unknown quantity, I was tarred and feathered by angry throngs insisting that it won't matter because of the defensive line. With emotions high, I wanted to get to as objective of a truth as possible.

"The argument basically comes down to two perspectives: either the secondary helps out the line by holding coverage to force coverage sacks, or the line helps out the secondary by limiting the QB reads. By this reasoning, depending on which logic you follow, the Lions will either do great or be horrible, no in-between."

Actually, I think there's a pretty strong case to be made that the defensive line will help the defense as a whole be not-horrible. HOWEVER, the defensive line itself can't possibly be so good that the horrible coverage won't matter.

I tend to believe that the disruption, or lack thereof, by the defensive line, is the most important factor in the offense/defense interaction. However, if the corners are playing 12-15 yards off the wideouts, no amount of DL pressure in the world is going to prevent those uncontested receptions.

Peace

Ty

"The yards lost to Sacks SHOULD be included because this is exactly what you're trying to examine - How does the pass rush (measured in terms of Sacks) affect passing efficiency (measured in terms of NY/A)?"

That's close, but not quite. What I REALLY want to know is, how does pass rush (measured in some crazy metric that doesn't exist, like Average Time to Throw Before Eaten By DE) affect passing efficiency (measured in terms of NY/A)?

All I have to use is sacks, though, so that's what I used--and looking for a correlation between Sacks and a statistic (NY/A) that's computed with both Sacks and Sack Yardage as major factors is like looking for fish in a fish tank.

It wasn't a given that using raw Y/A instead of the sack adjusted NY/A would have guaranteed near-zero correlation. An increase in sack rate might have seen quarterbacks turn to screens, three-step drops, and other quick-release passing options to neutralize the rush; that would depress raw Y/A even without any actual sacks occurring.

THAT, I think, is what fans are hoping to see: an offense "playing scared" because of the fury of the pass rush,; the threat of sacks forcing the offense to play max protect, go into a shell, and eliminate the deep routes that might expose the cornerbacks.

Unfortunately, even if there were a strong correlation between increased sacks per attempt and decreased yards per attempt, I'm still not convinced that the Lions' defensive line will be SO GOOD that said correlation wil make up for how truly undermanned the CB position is.

Peace

Ty

Matt--

Oh, and by the way, thanks for the clarification on correlation! Looks like my conclusions are mostly correct, but the "practically zero" correlations are a little stronger than I thought, and the other ones are really quite strong.

Peace

Ty

As far as I understand it, statistical significance is based on sample theory. ie to what extent your findings from your 'sample' can be translated to the wider 'population'.

Given that generally you have all the data for previous years, your findings are valid within the data set.

In terms of extending them to future years (namely 2010) statistical significance will go up, as the standard deviation (the average distance between all your scatter plots) goes down and the sample size (number of plots) goes up.

The actual statistical formulas needed to work this out properly are beyond me though.

Top piece

Ty, I think the general idea here is a good one, but you may be losing the effect by looking at the year-by-year NFL data. You sort of hit on the problem when you stated your critical assumption. I think what you are seeing is how defenses and offenses are adjusting to each other and to the rule changes over time - not how specific teams benefit from being better at rushing the passer.

Maybe a better way to expose the effect is to look at individual teams in a given year. The hypothesis would be that teams that sacked the QB a lot gave up lower YPA (or also had a higher interception rate, or, ...).

The yearly average data that you use is more useful to allow comparisons across years. So, you would actually look at each team's differences relative to the mean of that year. You probably don't need to do that, though. One year of data is probably enough to show or disprove the effect.

I didn't read all of the comments so if someone else touched on this then I apologize...

However, what about down and distance? For instance, an improved d-line will be better against the run and force teams into 2nd/3rd and long more often (of course "long" is relative based on down. 2nd and 9 is "long" while 3rd and 6 or 7 could also be considered "long"). With teams having farther to go for a first down they have to run routes and route combinations that take more time to develop, thus giving the line more time to get to the QB which in turn could decrease passing efficiency.

Also, long touchdowns plagued the Lions last year based mostly on a lack of pass rush and having sub-par CB's covering receivers for 7 seconds (think Thanksgiving and Rodgers pass to Donald Driver). I am not quick to say that this bunch of corners is an upgrade from last year, but I can confidently say that the defensive line is better. Let's pretend those long touchdowns are cut in half (in terms of frequency), the team is easily in a few more games and pulls a few more wins. They're not down 2-3 touchdowns early in the game, don't have Stafford trying to win games by himself and throwing INT's, can run the ball and control the clock, etc.

Prior to drafting Stafford, Schwartz made the comment that the Lions reviewed all the coach's tape of Stafford's third down plays during his last two years at Georgia.

Schwartz didn't say they watched the entire games just the third downs. Thats a lot of splicing for the Lions' film department in Allen Park.

Which sort of segways into this statistical study. A lot of work went and is to be commended, but the data is too raw to be conclusive.

By raw, I mean the data doesn't differentiate between 3-4 defenses or 4-3. It doesn't differentiate between Tampa 2 or prevent. The input doesn't differentiate whether or not a team has the lead or is out of the game when compiling the statistics. It doesn't differentiate between playing outdoors or on artificial surfaces indoors. It doesn't differentiate between playing in inclimate conditions or playing in the desert or mile high air. Data in, data out - raw data in, inconclusive data out. Perhaps, to be more concise the input could be refined to only include the top x number of defenses each year for the period of analysis?

The NFL seems to be trending towards more teams going with a 3-4 defense. Why is that?

My guess is that teams currently with 3-4 defenses and those transitioning to 3-4 defenses have conclusive statistics that prove to them that the 3-4 is the best option. Lots of splicing going on around the NFL.

As everyone knows a lot of the 3-4 defenses have a blitzing LB that can attempt to pressure the QB from anywhere. The guy can move around from play to play, thus giving the defense a higher probability of at least rushing the opposing QB.

Logic would dictate that the less time the QB has to throw the brick defensive statistics will improve, because if the opposing QB, any opposing QB, goes up against the Lions defense the last couple of years they are assured a QB rating of 100+.

As an endnote this study doesn't indicate how much time the QBs have to throw the brick. Theres no difference indicator whether the QB has 3-4 seconds to throw the brick or whether the opposing QB can make dinner reservations before throwing the brick. So why would the Lions remain committed to a base 4-3 when on average the league is trending toward 3-4 defenses? My guess is the brass believes via taped evidence that pressuring the QB is a difference maker and they are going to attempt to do that by being bigger, faster and smarter.

Bad Axe Herald

Lies, Damned Lies, and Statistics (Rob), and Jim--

Yeah, projecting it forward, for the Lions, is coming up. I was going to do a two-parter where I take the NFL-wide trends and then apply it to the Lions, but with the feedback I'm getting, this may be a three-parter.

Jim's idea, I think, is the correct part 2. Next, I'll need to look at team-by-team stats over the last couple-three years. I might even be able to get QB pressure data, as well. If trends can be identified from that, part 3 will be projecting the Lions' data forward.

Peace

Ty

LionsFanRoc--

There may well be an increase in pass rush effectiveness on third down, and that might have a big impact on the game. I did note that an increase in sacks will definitely help the scoring defense. Stopping drives on third down is absolutely critical, and something the Lions have been historically bad at.

However, when the corners are as helpless as they were last year--and I think they'll be as bad, or worse, this year--it still matters. Look at what Drew Brees and the Saints did in Week 1: two quick scores in the first five minutes, and the game was already over.

Brees went 26/34 for 358 and 6 TDs that day. He quite literally scored at will. If the Lions' DL gets a step closer to him on every play, what does that change? If they get an extra sack or two, what does that change?

The other unfortunate reality is that "long passing TDs" don't always come from long-developing routes or seven-step drops. Often, it's a wideout catching the ball in open space and beating the only man who's on him, or a blown coverage, where the corner thinks he has help but doesn't. The only fix for those is better secondary play.

Peace

Ty

Anon--

Er, actually, they did watch every snap, not just third downs:

http://sports.espn.go.com/nfl/draft09/news/story?id=4097641

"We've seen every pass he's thrown in the last two years, and that's where you learn about his decision-making ability."

So there's that.

The rest of your post is well-taken, though. There are two real reasons I started with leaguewide data:

1) It was what I could get my hands on without a lot of effort.

2) It captures football-wide trends, independent of scheme.

Those who read my in-season stuff know that scheme-on-scheme interaction is something I focus heavily on, and something I don't think gets enough attention in NFL analysis.

However, I didn't want to intensely study the Lions' defense last year, draw some wild conclusions based on one or two outlier games, and project it forward. Remember, the Lions' 2008 defense was the worst defense ever assembled. They were significantly better in 2009--and arguably, still the worst defense in the NFL. Examining data from that defense, and trying to define systemic trends and effects to apply going forward, wouldn't have been a good idea.

By starting at the 50,000-foot-view, though, with leaguewide data over 20 years, we can see that there is weak inverse correlation between sacks & INTs and passing offense effectivness, but very strong inverse correlation between passes defensed and passing offense effectiveness.

Next, I'll drill down into team-by-team data, hopefully including pressures and/or hurries. This should confirm how well the broader trends hold up when applied to specific schemes, and should also capture the more detailed specifics we're looking for--the ones that will help us project the Lions' improvement from 2009 to 2010.

Peace

Ty

On statistical significance of correlations. I assume you conducted a Pearson's correlation (r) which is used with continuous variables. If that is the case all you need to know is your sample size (N), degrees of freedom (df) which is N-2, and the go to this chart

http://faculty.vassar.edu/lowry/tabs.html#r

go to the r to P calculator...in this case P stands for statistical probability and it is the probability that the correlation is due to chance...thus the lower the p the better. The typical bench mark is p < .05 (this means there is only a 5% chance the correlation is due to error)

type in the sample size (N), correlation coefficient (r), and the degrees of freedom (N-2), then click calculate

As a last note, it is best to use the two-tailed p...its more statistically robust...if you want to know why i can explain

Interesting stuff Ty.

It is pretty hard to get a handle on all the variables. Got something on the same subject coming up soon so this research was very timely. Probably link to your article if you don't mind.

BlueinGreer (I used to have a profile or something to comment with but damned if I can find it now)

Ty, I'm an infrequent visitor to your site but I always seem to enjoy your articles.

I'm wondering if there's not a simpler way of getting at what you're trying to ascertain. I know you're attempting to remain "generic" without highlighting particular styles of defense, but I'm thinking it might be more effective to simply find the top 5 (or whatever other number you choose) in overall pass defense for a particular period of time, then look at the personnel of those defenses. Yes, this would be subjective to a certain extent, but I also think there would be broad general agreement over the caliber of the players involved on each team, and you could pit the defensive line against the defensive backfield in each specific case to determine if there was a trend among those top teams.

I'm sure I'm being too simplistic somehow, but it would probably make for some good debate. I humbly submit it for your review...

Walt

Ty,

Very few statisticians consider statistical significance a meaningful indicator of the validity of a relationship. This is because small correlations can be statistically significant. The more important statistics you should focus on are the magnitude and direction of the effects (i.e., if the correlation is negative/positive and how large the correlation is).

One of the best indicators of nature of the relationship is the effect size calculation. You can obtain an effect size by squaring your correlation coefficient. This will tell you the amount of variability the variables contribute to each other. There's a lot of noise in NFL data so an effect size will tell you how much unique data is explained by the correlation alone.

Rule of thumb for effect sizes: small .2; medium .5; large .8

Hope that helps!

Anons various:

"On statistical significance of correlations . . ."

Wow, perfect, exactly what I was looking for! You killed it, and thanks for the link.

"Very few statisticians consider statistical significance a meaningful indicator of the validity of a relationship . . ."

Wow. You, my friend, also killed it. Thanks also for the perspective.

I think I now need to refocus the conclusions drawn above, then drill down into the team-by-team detail data to see if I can get closer to what's really happening. Thanks, folks!

Peace

Ty

Ty' another thing that might be interesting to look at is if there is a correlation between sack numbers and pass defended numbers, IE. did the teams with higher sack rates also have higher pass's defended numbers. this should help in the lack of hurries and pressures numbers, as it would show that a good pass rush made the QB less accurate (based on the assumption that higher sack numbers means more pressure on the QB on all pass plays)

Wow nice insight!!! Went in depth in a fashion most sports journalists would never even attempt, good job! Mark me down as a fan thats still clicking his heels and and saying the Dline is coming though haha...I Love this site!

Come talk Lions anytime guys, we need some fellow fans, its an upstart site with moderators for some team rooms needed, with a vision for insult free Lions talk and a spam/company advertisement free board!!! Put it in your favorites with the rest of all your favorite Lions sites like The Lions in Winter!

http://www.prosportsforums.com/forumdisplay.php?48-Detroit-Lions&order=desc

Regards,

Lions#20

Ty,

Let me say that when I have had a chance to read your posts I have really enjoyed them. I must have read this post three or four times. I was really interested reading your post because I have working on something similar myself, albeit with the goal of trying to isolate the contributions of individual defensive backs rather than weighing the relative merits of sacks versus interceptions for pass defense purposes. Anyway, I have self-taught myself a lot of statistics, so I definitely know where you're coming from where you're just starting to play around with using regression and football statistics.

First, as far as the R2's go, when you are dealing with football statistics, you cannot really put R2's into the 0.2 (small), 0.5 (medium), and 0.8 (strong) boxes. When you're doing any sort of meaningful measures, you are not going to get R2's that are much stronger tha 0.2. My SackSEER model actually only has an R squared as 0.42. The reason being is that football is an incredibly context-dependent sport with small sample sizes: there are 22 "non-specialist" starting positions and only 16 games in a season. If you think about what an R2 means: that it accounts for a certain percentage of the historical variation in a given statistic, then a statistic that accounts for 20% of the variation in another is pretty remarkable.

Second, in regard to the particular analysis, I do not mean to pile on to what has been mentioned in the comments, but I think that using year by year rather than team by team numbers is suppressing real trends that are relevant to your inquiry. I have a spreadsheet with about 350 team seasons loaded up and I have found that interceptions, sacks, and passes defensed (and in that order) correlate to good pass defense and are statistically significant. However, I am using a different metric to measure pass defense than you are which might partially account for the disparity in our results.

Third, I think in order to be balanced you really need to give passes defensed the same treatment that you give sacks. I know that interceptions represent incompletions too, as you note, but they introduce far less noise because they are relatively rare events. A team will have somewhere between two to three times more passes defensed than interceptions. If you factor out the incompletions caused by passes defensed, you might find that the relationship between passes defensed and NY/A evaporates in the same way that sacks do.

Fourth, I think you need to be a little bit careful about dismissing a possible relationship just because you don't get a high correlation (I am actually not sure what you are using to measure correlation. Is it the slope of the line, the r squared, or the Pearson Correlation Coefficient?). "Statistical Significance" is actually a pretty high standard to meet, so when you have an r squared like .068, that might actually represent a real relationship even though it is small and might not be significant. For instance, it seems counterintuitive to me that a good pass rush does not improve a pass defense. Why would teams like the Dallas Cowboys pay players like DeMarcus Ware millions of dollars if sacking the quarterback doesn't improve your pass defense?

Finally, I am glad that somebody else noticed the bizarre passes defensed numbers that pro football reference spits out for 2002. I am pretty sure that the problem is with PFR's database. I went through all of the defensive backs that played in 2002 and found that PFR recorded "0" passes defensed for a few players that had passes defensed in the high teens. That might be a little extreme for the kind of stuff that you are doing. I think for what I have to do now I will have to go through and do the same for other players and I am not looking forward to it.

Anyway, tremendous read. I really hope that you do a follow-up post so I can see where you ultimately go with this.

I would think there would be a differance between a sack caused by a standard 4 man rush and one caused by a blitz, with a team that blitzes regularly having a high sack total but also a hight net yards per attempt.

Post a Comment